Let’s pretend that the United States economy is a football team. The coach calls the play. The running back runs right up the middle and is thrown for a loss. What does the coach do on the next play? Run the ball up the middle for a loss. And the play after that? Run the ball up the middle for a loss. And the play after that? Run the ball up the middle for a loss.

Other teams see what’s happening to the U.S. economy. So what do they do? Run the ball up the middle for a loss. In Japan, in Europe and elsewhere the losses mount. What’s the conclusion?

- Running the ball up the middle every play will result in a loss, or

- We need to run the ball up the middle more often.

The answer, if you’re paying attention to central banks and the actions of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is, of course, B., as logic and politics rarely travel on the same highway.

The answer, if you’re paying attention to central banks and the actions of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is, of course, B., as logic and politics rarely travel on the same highway.

Formerly the world’s number two economy behind the U.S., Japan’s future couldn’t have been brighter back in the ’80s, when “Japan Inc.” was all the rage. Today, if there really was a Japan Inc., it would have long ago declared bankruptcy. The “Land of the Rising Sun” has become the “Land of the Setting Sun.”

“I’d say it’s time to call Abenomics a failure,” according to Jeff Kingston, a professor of politics at Temple University in Tokyo who was quoted in The New York Times. “The recession means Abe has failed to deliver on growth, and he has whiffed the structural reforms. All that is left is disappointment.”

QE and Spending

Japan has followed the United States down the quantitative easing rabbit hole with the same results – a low rate of growth, fewer high-paying jobs and, of course, a booming stock market to cite as proof that quantitative easing works.

Quantitative easing is almost always accompanied by government “stimulus” spending. That’s one area where Japan has the U.S. beat – though not by much. That’s difficult to do, considering the $1 trillion+ budget deficits the U.S. has been running since President Obama took office. This year, the U.S. federal deficit is down to a half trillion dollars, but it remains far from being under control.

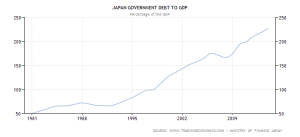

In Japan, government spending is 42% of gross domestic product (GDP), while in the U.S., government spending is over 40% of GDP, according to the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom. Look at the chart above, though, showing the increase in government debt as a percentage of GDP and you may conclude that Japan is the new Greece.

Government debt has soared from 50% of GDP in 1981 to about 230% of GDP today.

So what has all of that government spending and quantitative easing bought? A triple-dip recession, with GDP now falling back to what it was before Abenomics began.

Japan’s economy was expected to grow 2.2% in the third quarter. Instead, it had an “unexpected” drop of 1.6%. So has the prime minster concluded that massive government spending and easy money are bad for the economy? No. Instead he’s calling an election to gather public support for more of the same.

“This is getting hard to believe,” according to David Stockman. “The announcement that Japan has plunged into a triple dip recession should have been lights out for Abenomics. But, no, its madman prime minister has now called a snap election to enlist more public support for his campaign to destroy what remains of Japan’s economy. And what’s worse, he’s not likely to be stopped by the electorate or even the leadership of Japan Inc, which presumably should know better.”

U.S. Catching Up

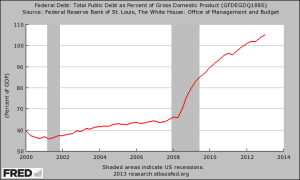

You could argue that the U.S. is in better shape than Japan. After all, federal debt in the U.S. is about 105% of GDP, which is less than half of Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio. But Japan had a head start with its “lost decade,” which is quickly becoming its “lost two decades.”

And the U.S. is doing its best to catch up. Note that the slope of the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio is steeper than Japan’s. And it could just be that the U.S. disguises its debt better than Japan. The U.S. chart doesn’t include state and local debt, and it doesn’t include unfunded liabilities for programs such as Medicare and Social Security.

So if Keynesian economics doesn’t work, why are world leaders still relying on it? Why don’t they try other ways of stimulating the economy?

One reason is that doing so would be admitting they are wrong. That just doesn’t happen in politics. Another is that they’re government employees; they’ve been bred for Keynesian economics. It’s all they know. The overriding reason, though, is that more money for government programs means more power. When the government becomes big enough, you can even ignore Congress and rule by executive order.

So government policymakers will continue to follow Keynesian policies until, as The New York Times put it, “All that’s left is disappointment.”