The idea was logical enough.

Reduce interest rates, making housing more affordable, which would produce a recovery in the housing market. The housing market was at the heart of the financial crisis, so bringing the housing market back to health would, presumably, bring the economy back to health.

That conclusion was sound, too. Housing is a leading economic indicator, so a recovering housing market should mean a recovering economy.

But in economics, as in life, things don’t always go as planned. The housing market still hasn’t recovered. And, while low interest rates may have given housing prices a boost, they have not increased home ownership.

ownership.

In addition, government programs have only made matters worse, while costing taxpayers a bundle.

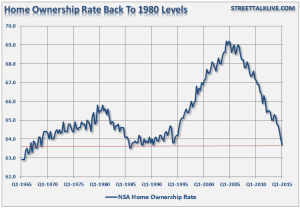

As Lance Roberts noted on his Street Talk blog, “trillions of dollars have been directly focused at the housing markets including HAMP, HARP, mortgage write-downs, delayed foreclosures, government backed settlements of ‘fraud-closure’ issues, debt forgiveness and direct buying of mortgage bonds by the Fed to drive refinancing and purchase rates lower.”

settlements of ‘fraud-closure’ issues, debt forgiveness and direct buying of mortgage bonds by the Fed to drive refinancing and purchase rates lower.”

Yet, as the chart shows, the net result has been that the home ownership rate has dropped to where it was in 1980.

ownership rate has dropped to where it was in 1980.

Why did government help ” fail would-be homeowners?

” fail would-be homeowners?

Home ownership will never be universal. For one thing, in spite of the federal government’s insistence to the contrary, not everyone can afford a home. Those that can’t eventually are foreclosed upon. No-doc loans and feel-good programs like the Community Reinvestment Act may help put people in their own homes, but if they can’t afford to pay off their mortgages, they will eventually lose their homes – and most likely end up poorer than they were before the government became involved.

and feel-good programs like the Community Reinvestment Act may help put people in their own homes, but if they can’t afford to pay off their mortgages, they will eventually lose their homes – and most likely end up poorer than they were before the government became involved.

People who don’t work can’t afford homes . The real driver of home ownership and of economic growth is employment. When people have good, well paying

. The real driver of home ownership and of economic growth is employment. When people have good, well paying jobs

jobs , they will buy houses. And they will do so on their own, without government help.

, they will buy houses. And they will do so on their own, without government help.

As we’ve reported in the past, the unemployment rate has fallen primarily because fewer people are looking for work – and many who have found jobs are working part-time. With more than 100 million Americans not participating in the labor force, that’s 100 million Americans who are unlikely to be purchasing homes.

“Full-time employment is what ultimately drives economic growth, pays wages that will support household formation, and fuels higher levels of government revenue from taxes,” according to Roberts, who also wrote, “With wages remaining suppressed, 1 out of 3 Americans no longer counted as part of the work force or drawing on a Federal subsidy, the pool of potential buyers remains tightly constrained.”

household formation, and fuels higher levels of government revenue from taxes,” according to Roberts, who also wrote, “With wages remaining suppressed, 1 out of 3 Americans no longer counted as part of the work force or drawing on a Federal subsidy, the pool of potential buyers remains tightly constrained.”

Fewer of those who work can afford homes . Taxes are up, personal income is down and many people are earning less than they did before the financial crisis.

. Taxes are up, personal income is down and many people are earning less than they did before the financial crisis.

Institutional investors have been the biggest beneficiaries. Banks were incentivized by the federal government to take on risky loans and to pass the risk on to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Fan and Fred were incentivized to add to their mortgage portfolios, regardless of the risk.

and to pass the risk on to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Fan and Fred were incentivized to add to their mortgage portfolios, regardless of the risk.

When people who couldn’t afford their homes stopped paying their mortgages, Fan and Fred were stuck with huge blocks of properties, which they unloaded to institutional investors. The institutional investors then rented them out.

“Speculators have flooded the market with a majority of the properties being paid for in cash and then turned into rentals,” Roberts wrote. “This activity drives the prices of homes higher, reduces inventory and increases rental rates which prices ‘first-time homebuyers’ out of the market.”

drives the prices of homes higher, reduces inventory and increases rental rates which prices ‘first-time homebuyers’ out of the market.”

In other words, government policies designed to turn renters into home buyers have instead created more renters. But at least institutional investors made money.

buyers have instead created more renters. But at least institutional investors made money.

Moving Forward

The housing market has marginally improved from where it was when the financial crisis hit in 2008. But trillions of dollars should buy more than marginal improvement – and Fed policy has made the future look grime.

more than marginal improvement – and Fed policy has made the future look grime.

If interest rates had remained closer to normal, Fed supporters would say, the housing market would be in worse shape than it is today. That’s doubtful, as market forces would eventually stabilize and improve the market. Today, the fear of rising rates is likely to have a disastrous impact. It rates had remained near normal, that fear would not exist, because we would be accustomed to higher rates.

would say, the housing market would be in worse shape than it is today. That’s doubtful, as market forces would eventually stabilize and improve the market. Today, the fear of rising rates is likely to have a disastrous impact. It rates had remained near normal, that fear would not exist, because we would be accustomed to higher rates.

Roberts foresees the speculative buyers turning into sellers. And when that happens, there will not be a large enough pool of qualified buyers to absorb the inventory – and, as mortgage rates trend

– and, as mortgage rates trend upward, fewer qualified buyers will be available

upward, fewer qualified buyers will be available . Increased supply with fewer qualified buyers will cause prices to drop again.

. Increased supply with fewer qualified buyers will cause prices to drop again.

What could be done to boost employment and help

and help the housing market? Keynesian wishful thinking is no substitute for pro-growth government policies. Tax reform would help

the housing market? Keynesian wishful thinking is no substitute for pro-growth government policies. Tax reform would help , as would approval of trade agreements (ironically, most Republicans are supporting and most Democrats are opposing President Obama’s request for trade

, as would approval of trade agreements (ironically, most Republicans are supporting and most Democrats are opposing President Obama’s request for trade promotion authority).

promotion authority).

Perhaps the most important pro-growth action that could be taken would be to ease the regulatory burden on business. Dodd-Frank’s provision to “protect” would-be homebuyers, resulted in a drop in mortgage approvals, while Obamacare’s mandates have resulted in a huge increase in part-time workers.

approvals, while Obamacare’s mandates have resulted in a huge increase in part-time workers.

It’s doubtful that a pro-growth agenda will be on the table anytime soon . So it’s doubtful that we’ll see a full economic recovery anytime soon.

. So it’s doubtful that we’ll see a full economic recovery anytime soon.