What’s free about trade?

To put the free in free trade, the United States and its trading partners would have to eliminate special treatment for all products.

Yet even in a country that invented and thrived on free enterprise, free trade has been more myth than reality for many years. There have been subsidies for farmers, tariffs on goods even when they are being imported from our allies, quotas and other concessions to special interest groups. And there has been currency manipulation, making currency weaker to make exports cheaper for consumers in importing countries.

These less-than-free trade practices have been practiced not only by the United States, but by countries throughout the world. But free trade is relative and the United States is more open than most countries.

China’s Unfair Trade Practices

The worst offender, though, is the Chinese government, which regularly engages in theft. And it’s theft in which American businesses are complicit — even though they’re the ones being robbed.

To do business with China, American companies regularly share their intellectual property with China. For years, China has also been ignoring patent law and reverse engineering American products, so that it can produce similar products without the years of research and billions of dollars that have gone into developing them.

The list of unfair trade practices by China is long, but given China’s population of 1.4 billion people, many American businesses accept unfair treatment as a cost of access to China’s developing market.

As President Trump’s strategy for China evolves, it’s clear that negotiating fairer trade practices is a big part of it.

Initially, the Trump Administration imposed tariffs on washing machines and solar panels, then added tariffs to steel and aluminum. Next, tariffs were imposed on $50 billion worth of Chinese goods, focused almost exclusively on industrial goods and intermediate parts used in consumer products. In September, the administration added a 10% tariff on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods China exports to the U.S.

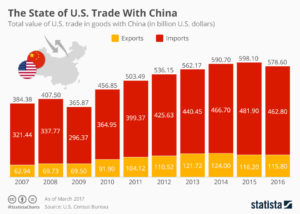

While tariffs typically result in retaliation and can lead to a trade war, China has more to lose than the U.S., as the U.S. imports more than a half trillion of Chinese products a year, while it exports only $130 billion worth of U.S. goods to China. This $375 billion trade deficit, as of 2017, is the largest in the world.

In addition, while the U.S. economy is currently growing at its most rapid rate since before the financial crisis, growth has been slowing in China.

President Trump’s strategy appears to be to negotiate trade deals with other countries first and then to use those agreements as leverage with China. The administration initially negotiated a deal with South Korea and more recently negotiated the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which we will discuss in our next post.

Plans call for trade negotiations with the European Union and Japan next, potentially using the USMCA as a template.

One aspect of the USMCA is especially noteworthy, when considering future negotiations with China. According to the South China Morning Post, “it gives Washington virtual veto power over any bilateral deal Canada or Mexico may wish to reach with ‘a non-market country,’ for which read China. Any such deal could mean the end of the USMCA for that country.”

In other words, the U.S. is seeking to line up allies before it negotiates a trade deal with China.