With the current recovery stretching to 113 months, it’s easy to forget that the economy is, and always has been, cyclical.

Cycles can be manipulated to some degree, but they cannot be avoided indefinitely. Many credit the Federal Reserve Board’s initial lowering of interest rates for helping to end the Great Recession and start the recovery. And just as it appeared that a recession was coming in 2016, tax reform and deregulation provided a boost to economic growth, extending the recovery.

As a result, the current recovery is the second longest recovery on record and, if it persists until July 2019, it will break the record of 10 years held by the recovery that took place from 1991 to 2001.

The current recovery is widely expected to become the longest on record, but it won’t go on forever. The recovery is so old, it should be eligible for Medicare. And its age is showing, as the signs that it is slowing down are increasing.

“Equity markets are well down from early October and yields on U.S. Treasury bonds have fallen, indications of diminished investor expectations for growth and inflation,” according to The Wall Street Journal. “Business investment data have softened, the trade deficit has widened and concerns over global growth are mounting.”

While few believe a recession is near, economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal estimate that economic growth rate will slow to 2.5% by Q1 ’19 and 2.3% by Q3 ’19. The Fed is forecasting that growth will slow to 1.8% by 2021.

Signs of a Slowdown

While 2018 should be the first year since the Great Recession in which the economy grew by more than 3%, signs of slower growth are mounting:

Employment. Today, there are more jobs available than there are people looking for jobs. As a result, many employers are either delaying expansion plans or increasing wages to attract qualified workers. Delaying expansion and increasing wages, which lowers profits, stunt economic growth.

Conversely, increasing wages along with low inflation mean consumers have more money to spend — which is the most important driver of economic growth.

But employment levels may have already peaked.

In November, employers slowed their hiring, adding a seasonally adjusted 155,000 jobs. That brings average growth for the past three months down to 170,000 new nonfarm jobs a month, which is the slowest three-month growth rate in a year.

And while the widely reported U-3 unemployment rate remained unchanged at 3.7%, the U-6 rate rose to 7.6% from 7.4% the prior month. The U-6 rate includes those who have given up looking for work and part-time workers; the U-3 rate does not.

The unemployment rate is still lower than what the Federal Reserve Board previously considered to be full employment and it’s far lower than it was after the Great Recession, when the U-3 rate reached double digits.

Eventually, though, the unemployment rate will rise again.

Corporate profits. Profits have a major impact on the stock market and high profits have been a major reason that the market performed well last year.

After being down 1.1% for all of 2016, corporate profits rose 3.2% in 2017, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. And they’ve continued rising since then, jumping 3% in the second quarter of 2018 and 3.4% in the third quarter.

“U.S. corporate profits boomed in the second quarter, boosted by large tax cuts and stronger economic growth than initially reported,” The Wall Street Journal reported in August.

The Commerce Department reported in August that its broadest measure of after-tax profits across the U.S. rose 16.1% in the quarter ended June 30 from a year earlier, the largest year-over-year gain in six years.

But now the recovery may become a victim of its own success. With corporate profits having reached their highest level ever, they’re not likely to grow as rapidly moving forward. When comparing profits quarter over quarter, results will not look as impressive.

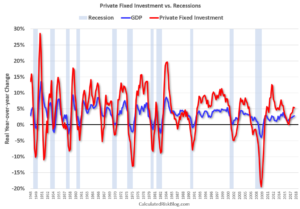

Business investment. When President Obama was in office, the Federal Reserve Board bought trillions of dollars’ worth of bonds to bring interest rates close to zero under the assumption that lower rates would become a catalyst for business investment.

“Quantitative easing,” as the Fed called it, didn’t drive more business investment, but tax reform did. Among other things, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act lowered the corporate tax rate from 35% — the highest in the developed world — to 21%.

But the boom in business investment seems to have ended.

“The White House projection of sustained 3% growth hinges on a business-investment boom,” according to The Wall Street Journal. “It looked like that was happening early in the year. Business investment grew at an 11.5% rate in the first quarter, with gains across many categories, including machines, intellectual property and big structures. But it has faded since, registering just 0.8% growth in the third quarter. That includes a drop in investment in structures such as oil-and-gas rigs, which had been a big driver of growth.”

A recession does not appear to be imminent, but it does appear that the U.S. is in the late stage of its recovery. Economic cycles, like death and taxes, cannot be avoided forever.