Even with interest rates just above zero for seven years, and government spending regularly producing deficits of $1 trillion a year, economic growth was well below average throughout the Obama Administration.

In fact, the long, slow recovery was showing signs of collapsing toward the end of President Obama’s second term. In Q3 ’15, the economy grew only 1% on an annualized basis and in Q4 ’15, growth slowed to just 0.4%.

In comparison, the economy has grown at an average rate of 3.3% since the end of World War II. From the time the recovery began in June 2009 through the end of the Obama Administration, growth averaged just above 2%. Since Q2 ’17, it has averaged more than 3%.

What’s made the difference? With support from Congress, President Trump was able to pass tax reform and pursue deregulation, which extended and strengthened the recovery.

“During his time in office, the economy has achieved feats most experts thought impossible,” CNBC reported in September. “GDP is growing at a 3 percent-plus rate. The unemployment rate is near a 50-year low. Meanwhile, the stock market has jumped 27 percent amid a surge in corporate profits.”

So, even with less stimulus spending and higher interest rates, the economy has grown at a faster rate. Also consider that the baseline for growth during the Obama Administration was low, as he began his presidency during the Great Recession. Coming out of a period when the economy was shrinking — what economists call negative growth — the economy should have expanded at a faster rate.

Yet today, 113 months into the expansion, the economy appears to be concluding its first year of 3.0+% growth since before the Great Recession.

Paying the Price

President Obama has taken credit for today’s economic growth, but in reality he may be responsible for the next recession. Because interest rates were reduced to just above zero to boost the economy, they are now being “normalized” to prevent the economy from overheating.

After seven years of zero interest rate policy, the Federal Reserve Board has been raising interest rates, which has been a major cause of recent volatility in the stock market — just as lowering rates boosted stock prices.

In addition, as we’ve noted, it’s no coincidence that business investment is falling off as interest rates are rising.

If, as many experts claim, quantitative easing was a catalyst for the recovery, could it be that the quantitative tightening that is raising interest rates will be a catalyst for the next recession?

In addition to raising rates, the Fed has begun reducing its bloated portfolio of bonds, which soared from under $1 trillion to $4.2 trillion when the Fed purchased bonds to lower interest rates.

But the Fed still holds more than $2 trillion in long-term Treasuries, which is holding down long-term interest rates at the same time the Fed’s rate hikes are causing yields on two-year Treasuries to increase.

The net effect is a flattening of the yield curve, which is now practically inverted. Investors appear to be interpreting the inverting yield curve as a sign that a recession is coming, as the yield curve typically becomes inverted before a recession.

Increasing Debt

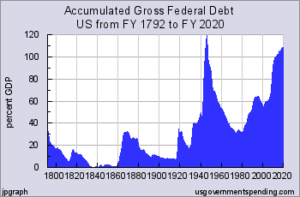

Stimulus spending during the Obama years also doubled the federal debt to about $20 trillion.

While the Trump Administration continues to add to the federal debt, which is now approaching $22 trillion, it is doing so at a slower rate.

Some have criticized tax cuts included in the tax reform legislation for increasing the debt, but, as we’ve previously noted, added revenue from economic growth will offset 88.2% of the estimated 10-year cost of the tax cut, according to The Wall Street Journal. Even the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found that growth results from tax cuts will cover the majority of the costs.

In contrast, the CBO found that the tepid economic growth from 2014 through 2016 cost $3.2 trillion in projected 10-year revenues — almost five times the amount of revenue than was gained by the 2013 tax increase.

While the debt created by lower revenues and increased spending continues to grow, so does the annual cost of servicing it.

Phil Gramm, former chair of the Senate Banking Committee, and Michael Solon, a partner in U.S. Policy Metrics, addressed this issue in The Wall Street Journal: “If the economy continues to grow at the normal postwar rate, growth-driven federal revenues will overwhelm the costs of the tax cut, paying for virtually all of its originally projected 10-year revenue losses in just five years. But if Treasury borrowing cost normalizes to 3.2% over the next five years, the cost of servicing the federal debt will more than double, from $316 billion this year to $666 billion in 2023.

“If borrowing costs rose to 4.8% over the next five years, federal debt-servicing costs would more than triple, reaching $1.1 trillion in 2023. In that scenario, the cost of servicing the $7.5 trillion increase in the public debt incurred during the 2009-16 period alone would cost $362 billion—more than the current cost of servicing the entire federal debt.”

Still, thanks to growth generated by tax reform and deregulation, the U.S. is in a much better position than the rest of the world.

Europe and China continued to follow loose monetary policy, even in some cases adopting negative interest rates, while the U.S. raised rates. If a recession comes and it becomes necessary to reduce interest rates again, the U.S. at least has rates that are high enough so that they can be lowered.

Europe and China are not so lucky. Their monetary policy has left them no room to lower rates further. Maybe they will have to resort to tax reform and deregulation.