A previous post was based on the phrase, “Winter is coming,” made popular by “Game of Thrones.” Our point was that, just as “winter is coming,” so is a recession – but, in both cases, we don’t know when.

As “Game of Thrones” enters its final season, little is known about what will happen – allegedly there were even anti-drone devices during filming and fake scenes shot to keep the plot secret – but it’s pretty obvious that winter will finally be coming to Westeros. After all, it’s the final season and if it doesn’t come now, winter won’t be coming.

Meanwhile, here in the real world, we need to change the phrase to, “Winter is still coming,” as it’s still unclear when a recession will arrive.

By the time summer arrives, the current recovery will become the longest ever. No one – not even Paul Krugman – is predicting that won’t happen. While a historically long recovery should be no surprise coming out of the Great Recession, some suggest the length of the recovery is irrelevant. There’s a difference between being old and being dead, and this recovery was given new life with tax reform and deregulation. So it could continue for some time yet.

But even the United States, which has the world’s strongest historical relationship with capitalism, is subject to economic cycles.

Inverted Yield Curve

Some see the recently inverted yield curve as a sign that a recession is nigh; they see it as a sign that, like “Game of Thrones,” the recovery is ending. Depending on your feelings about “Game of Thrones,” both events could reduce your quality of life.

But an inverted yield curve doesn’t guarantee a recession. It’s just a sign. To date, the yield curve has inverted for yields on three-month and six-month Treasuries, but not for two-year Treasuries, which are typically used to determine whether the yield curve has inverted. And when a recession does occur after an inversion, it typically takes 11 months to two years, depending on which study you read.

Why the yield curve inverted is also important to consider. The negative interest rate policies of the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan contributed to the inversion of the U.S. yield curve, because low or negative yields outside the United States make U.S. Treasury bonds more attractive. The added demand causes Treasury prices to rise and yields to fall.

Slower Growth

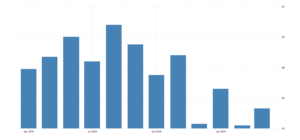

While a recession doesn’t appear to be imminent, neither does another quarter of 3% growth. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow is forecasting that gross domestic product (GDP) will grow at a rate of just 1.2% in the second quarter.

Fed forecasts have typically underestimated growth since 2016, just as they overestimated growth during the Obama administration, so growth may still be higher than GDPNow’s projection. There are plenty of signs that the economy is slowing down, but some of the evidence is contradictory and some of the reasons for sudden slowness may be temporary.

Consider, for example, the manufacturing purchasing managers’ index (PMI). By one read, from IHS Markit, the PMI for March fell below expectations of 53.5 for March with a reading of 52.5, which was a 21-month low. Anything above 50 indicates continuing growth.

Conversely, the more recent report from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) found that PMI rose to 55.3 – up from 54.2 in February, which had marked the PMI’s lowest level since November 2016. The consensus forecast was 54.2, with a range of 53.0 to 55.5, so it was at the high end of the range.

And so a recession is still coming. But, unlike winter, we don’t know when.