We can debate how much impact massive Fed intervention had on the economy as it recovered from the Great Recession, but one thing that’s undebatable is that the Federal Reserve Board has swelled its power as much as it has its portfolio.

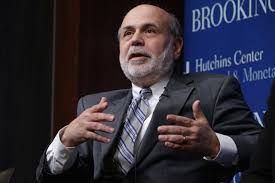

Over seven years, starting during the Great Recession under the direction of Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, the Fed bought more and more bonds until its portfolio grew from less than a trillion dollars to $4.5 trillion.

Most government bodies would envy a central bank that can quadruple its portfolio in the name of creating a recovery. The recovery did, indeed, come quickly, but with 2% growth in a good year, it didn’t feel like a recovery. And how much impact the Fed’s monetary intervention had is debatable.

The Fed was, however, very successful at jacking up stock prices. And that happened precisely because the economy was performing well below expectations. With interest rates near zero percent, investors moved more and more money into the stock market, as it was perceived to be the only place to make money.

When the economy underperformed, the Fed would buy more bonds, which would lower interest rates even further, drawing even more money into the stock market and causing stock prices to increase.

Back to Fundamentals? Not Quite.

Rewarding investors for economic underperformance – like punishing them because the economy is performing well – is perverse. Historically, the stock market has reflected fundamental performance. When profits are high, stock prices have increased and when they are not, they have decreased.

With deregulation and the passage of tax reform, the economy improved and we enjoyed three percent growth. Stock prices continued to rise. It appeared that fundamentals were once again determining market performance.

That changed in November 2018, when positive economic news caused stock prices to drop. Then a rate increase in December further hampered the market.

This year, the Fed and other central banks reversed direction. With economic growth appearing to slow globally, central banks globally signaled that they would begin to reduce interest rates yet again.

The U.S. is at least able to decrease rates, having increased them nine times since they were near zero. Europe and Japan, though, have no such comfort zone. Based on Barclays data, The Financial Times reported in June that almost $12 trillion of investment grade corporate and government bonds have negative yields, predominately in Europe and Japan.

Regardless, the markets are once again in the Fed’s control. Today, whenever there is any implication by the Federal Reserve Board that interest rates will go down, the market reacts positively. Any implication they will go up – e.g., positive economic new – they react negatively.

Most recently, before its July meeting, the Fed signaled that it would likely reduce interest rates by 0.25% (25 basis points) when it met. Markets reacted negatively, even though the Fed also signaled an openness to additional cuts, because wishful thinkers were hoping for a 0.5% cut.

Anyone following Fed behavior might have noticed that a cautious approach is being taken, as rate increases have typically been by 0.25%. Why would rate decreases be any different?

The net result, though, is that the legacy of former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke is that the Fed continues to have an enormous impact on our markets – and that news that’s good for the economy is bad for the markets.