Part two of a two-part series on the Fed’s approach to inflation.

In our last post we noted the Federal Reserve Board’s obsession with trying to achieve 2% inflation.

Not only has the Fed failed to reach its arbitrary goal for inflation, but its method for measuring inflation practically ensures that it can’t reach its goal.

The Fed uses the personal-consumption-expenditures price index to measure inflation, but new research by economists James Stock of Harvard University and Mark Watson of Princeton University shows that nearly half of prices in the index don’t respond to changes in economic activity.

Some prices, such as housing prices, typically rise faster when the economy is strong and growing, but others, ranging from durable goods to healthcare, are insensitive to rising or falling demand.

Why the Fed still uses the personal-consumption-expenditures price index as an inflation gauge is a mystery, given that its own economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found in 2017 that “acyclical” goods and services made up 58% of that index.

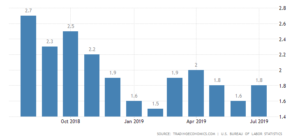

“The cyclically sensitive components of core inflation, which excludes food and energy, have accelerated to 2.33% in the 12 months through May from 0.41% in mid-2010,” according to the San Francisco Fed, “just as falling unemployment would predict. But that has been offset by falling inflation in acyclical categories — such as health care, financial services and most goods — which has slowed to 1.04% from 2.26% in the same period.”

So is it any wonder that the Fed has been unable to achieve its goal of 2% inflation even after years of trying?

Lowering Interest Rates

If the Fed lowers interest rates in the hope that increasing economic activity will boost inflation, it will likely continue to be disappointed – especially if it continues to lower them by just 25 basis points. A larger decrease could have an impact, since prices of many goods are still affected by supply and demand.

“For decades, mainstream economists have seen inflation as determined by slack – that is, spare capacity – in labor markets and the broader economy, according to The Wall Street Journal. “Too much slack should cause lower inflation; too little should drive up prices. This is captured in the Phillips curve, which shows an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation.”

We’ve previously noted that the Phillips curve hasn’t worked for years. In the 1970s, we had stagflation – high inflation in spite of a stagnant economy and high unemployment.

Today we have low unemployment as well as low inflation. Unemployment is close to its lowest point in half a century and we’re experiencing the longest expansion on record. Last year, American corporations had record profits. So why is the Fed worried that prices aren’t high enough?