Part one of a two-part series on the repo market.

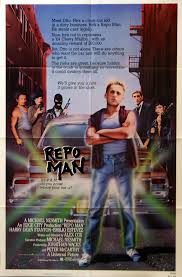

“A lot o’ people don’t realize what’s really going on. They view life as a bunch o’ unconnected incidents ‘n things. They don’t realize that there’s this, like, lattice o’ coincidence that lays on top o’ everything.”

Miller in “Repo Man”

It’s apt that The Financial Times and other media refer to the repurchase (aka “repo”) market as “the bond market’s plumbing.”

People don’t notice plumbing or talk about it if it’s working properly. In September, a lot of people noticed and talked about the repo market, which saw interest rates spike and an intervention by the Federal Reserve Board.

“My initial reaction was fear,” Hugh Nickola, head of fixed income at Gentrust told MarketWatch. “There’s really nothing more important than the functioning and transparency of financing markets.”

While most people have never even heard of the repo market, like plumbing, it plays an essential role. On a typical day, it enables banks and investors to borrow more than $1 trillion in cash overnight or for a short period using U.S. Treasuries as collateral.

That’s a lot of cash changing hands and keeping the financial system operating. Banks use that cash to finance loans and execute trades. Without it, the financial system would seize up and be illiquid. Banks would react by selling assets, such as corporate debt, and reining in their lending.

But increasingly large banks have been hoarding repo market cash. In fact, the five largest banks hold more than 90% of it, according to The Wall Street Journal.

When funds run low, rates spike. This hoarding recently drove borrowing costs higher for smaller firms, as the overnight repo rate jumped from about 2.25% to as high as 10%. This repo madness happened even as the Federal Reserve Board was pushing the federal funds rate down to a range of 1.75% to 2%.

The repo rate typically mirrors the federal funds rate. And when it spikes upward, it typically causes the federal funds rate to increase.

On to QE4

To push the repo rate back down, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) directed the Open Market Trading Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to inject “at least $75 billion” overnight daily from Monday, Sept. 23, 2019, through Thursday, Oct. 10, 2019. The Fed also reduced the interest it pays on excess reserves by 0.3%, reducing the incentive for banks to hoard the reserves.

The concept of the Fed buying billions of dollars’ worth of bonds a day to lower interest rates probably sounds familiar. We’re not experiencing another financial crisis, but we are seeing another round of quantitative easing (QE).

So what happened to all the cash created by QE1, QE2 and QE3?

“It’s been slowly evaporating,” according to Fortune, so QE4 is needed to create more cash.

The increased liquidity created with trillions of dollars in newly created cash from QE was supposed to encourage banks to lend more and boost economic growth. But total bank reserves have been decreasing since August 2014 and are not close to where they were in 2011.

Excess reserves peaked at $2.9 trillion in July 2014, but they have been shrinking since the Fed stopped buying billions of dollars’ worth of bonds each month. At the same time, the federal budget deficit has been increasing rapidly and Treasury debt has increased as a result.

Excess reserves have now dropped to $1.4 trillion and much of the money is tied up because of regulatory and liquidity requirements, according to The Wall Street Journal.

“One principle reason for that: an elevated level of government debt issuances in the past four years have sucked reserves out of the financial system,” according to Fortune.

If the repo market can’t function properly without the Fed buying massive amounts of bonds, it begs the question: How did it function before the financial crisis?

The last time the repo market sprung a leak was when the financial crisis began, and, as Fortune reported, “The repo market is looking a lot like it did on the precipice of the 2007 housing market crash.”

The Fed’s September intervention in money markets was the first of the past decade, according to The Wall Street Journal. However, during the 1980s the Fed used to intervene regularly – 100 to 200 times a year, Dave Leduc, chief investment officer of Mellon’s active fixed-income arm, told MarketWatch.