Part two of a two-part series on the repo market.

So the Federal Reserve Board buys bonds, creating trillions in cash, which it then pays interest on to banks, who hold it as excess reserves, even though they’re supposed to be lending it to other, smaller banks.

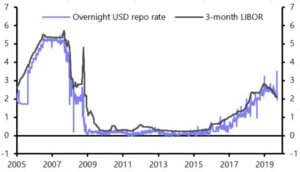

But the big banks have an incentive to hold the money, as they can make a risk-free profit from it. The big banks that are holding the repo market hostage must have asked themselves, “Why make unsecured loans at the federal funds rate when we can make secured loans, backed by the Fed, in the repo market at a much higher rate?” What would you do with your excess cash?

It looks like a case of big, powerful banks taking advantage of the little guys, but of course there’s more to it than that.

“As the Fed has increased lending in the repo market,” The Wall Street Journal noted, “it is reliant on a small group of bond dealers to recirculate that money through the financial system, increasing opportunities for channels to get clogged.”

And, barring changes to the current market structure, “concentration levels among the biggest banks are only going to get more concentrated,” James Tabacchi, president of South Street Securities, predicted.

Several other factors exacerbated the cash squeeze:

- Banks needed cash to pay for a recent high volume of Treasury debt sales.

- Companies used cash from money market accounts to pay corporate taxes and make the Sept. 15 deadline.

- Large banks may have held onto more cash than usual, because regulators typically examine their balance sheets at the end of fiscal quarters.

Another issue is a decline in the number of smaller firms that borrow from the larger dealers through the repo market and distribute the money more widely. Several such companies either closed or were acquired in recent years.

These smaller firms are at a disadvantage. They have less cash on hand and more difficulty raising it than large companies. Large primary dealers have more lines of credit connecting them with big banks, as well as trading relationships with money market funds.

No amount of bond buying will change that.

Fed Portfolio Will Get Bigger Again

Just recently, the Fed was seeking to shrink its bloated $4.5 trillion portfolio. Which was under $1 trillion when the financial crisis began. The Fed whittled it down to about $3.8 trillion, and by doing so may have been responsible for the 2018 end-of-year market meltdown.

So now the Fed’s portfolio will be growing once again – and, unless we find an alternative other than ongoing QE, is likely to become bigger than ever.

When the Fed again tries to reduce its portfolio, the impact on markets could be disastrous.

Then there’s the possibility of high inflation becoming a problem for the first time since the 1980s.

While previous rounds of QE didn’t spur inflation, perhaps because the economy was so weak, that may not be the case today. What happens if all of that new cash starts causing inflation to rise? It could hit the Fed’s 2% target rate quickly and keep on rising.

Given that the Fed hasn’t been able to achieve 2% inflation for long during its seven years of trying, I wouldn’t feel too confident about putting the Fed in charge to bring inflation back down to 2% once it exceeds the target level.

A better solution would be to control government spending and bring the federal deficit under control. Doing so would strengthen our economy and help future generations, but I’d bet big on ongoing QE instead.