Part one of a two-part series on interest rates and the federal debt.

Call it the interest rate paradox. If interest rates remain low or trend lower, the federal debt will increase. If interest rates rise, the federal debt will increase.

Why?

When interest rates are low, the federal government typically spends more, because the cost of borrowing is relatively inexpensive.

“The problems of 2008 were caused by an excess of debt,” according to Peter Schiff, CEO of Euro Pacific Capital Inc. “Artificially low interest rates encourage borrowing. After the financial crisis, the central bank doubled down. Now that the (Federal Reserve Board) has encouraged all of this debt, there is no way it can allow interest rates to rise.”

There is “no way” the Fed can allow interest rates to rise significantly, because, if they do, the cost of servicing the federal debt will increase proportionately. We will be taxed more and will spend more and get nothing in return, except for the privilege of continuing to borrow more money.

Servicing the Debt

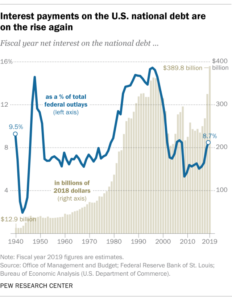

In spite of historically low interest rates, American taxpayers will pay $479 billion this year – about 10% of the budget – just to service the federal debt for the current fiscal year, which began October 1. The amount represents payment of interest, not principal. It is the minimum amount the U.S. can pay without endangering its stellar credit rating.

It’s money that could otherwise be used to create jobs, innovate, clean the environment, repair our infrastructure and make life better for everyone. It’s an investment with no return.

As recently as 2008, interest on the debt cost $253 billion and consumed 8.5% of the budget. As the Fed cut interest rates during the financial crisis, the cost of interest on the debt fell to $187 billion.

“From 2009 to 2016, it remained below $250 billion even though the national debt almost doubled as public spending skyrocketed and revenue plummeted. The recession led President Obama to create the most debt of any president,” according to The Balance.

Government spending was high under President George W. Bush, too, but trillion dollar a year deficits emerged during the Obama Administration, as government spending was used to stimulate the economy during the Great Recession. Keynesian economists and their followers believe that government spending stimulates the economy – but unlike spending in the private sector, government spending must be repaid.

Trillion dollar deficits are back, though, under President Trump. Tax reductions stimulated the economy, producing new revenue, but they did not completely pay for themselves, so they added to the deficit. So did new spending.

The Bipartisan Policy Center highlights the increasing costs of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid as major contributors to this year’s deficit, along with a 79% increase in Department of Education outlays “mostly due to an upward revision to the net subsidy costs of previously issued student loans.” That upward revision will cost taxpayers $40 billion.

The Bipartisan Policy Center also noted that the “net interest payments on the federal debt continued to rise, increasing by 14% ($48 billion) versus last year due to higher interest rates and a larger federal debt burden.”

So servicing the debt also adds to the debt, by pulling tax revenues from other areas and requiring more borrowing. If we didn’t have to pay interest on existing debt, the deficit this year would be practically cut in half.

As debt grows, so does the cost of paying interest on it, even when interest rates are low. Unless the budget is balanced, we are adding to the deficit continuously, which over time adds to the cost of servicing the debt and makes it more difficult to balance the budget.

According to the National Debt Clock, the national debt now exceeds $23 trillion. Add in unfunded liabilities for Medicare, Social Security and government pensions, and the national debt exceeds $120 trillion, according to Truth in Accounting, which estimates that federal debt for each taxpayer adds up to $787,000!

The problem is exacerbated by the country’s 77 million baby boomers, who are adding to the cost of Social Security and Medicare as they retire. Both are pay-as-you go programs, so as baby boomers leave the workforce, we have fewer workers supporting more retirees.