Part one of a two-part series.

“There is nothing normal about the nature of this cycle.”

Schwab market commentary

Don’t call what’s happening today the “new normal.” There is no “new normal.” In fact, there is no “normal” anymore.

For the economy to be “normal,” it must function in a manner that is common and typical. Anything else would be abnormal.

Today, America faces the triple threat of a pandemic, a severe recession and racial tensions that have resulted in nationwide protests, as well as rioting and looting in urban areas. Uncertainty about the future is high. And yet the stock market has been unfazed, recovering from an initial drop of about 28% (albeit, with a few bumps along the way).

There’s nothing normal about that.

Whether the economic recovery is “V” shaped, “U” shaped or “W” shaped, no one is doubting that there will be a recovery. COVID-19 will someday be history and Americans will likely once again abandon good hygiene. And the destruction of private property, including historic statutes, will likewise pass.

But the triple crisis will leave scars. What will the new abnormal look like?

Everyone will be broke. Consumers and corporations seem to be using the government as a role model for managing their finances. Total debt in the U.S. now adds up to $79.6 trillion, according to the U.S. Debt Clock.

The federal debt now exceeds $26 trillion. With the federal government spending $3 trillion to fight the pandemic — and the potential for at least another $1 trillion in spending — the federal deficit this year is already approaching $3.5 trillion and it continues to grow rapidly. Unfunded liabilities bring the total federal debt to more than $125 trillion — $811,000 for each taxpayer.

“Our latest projections find that under current law, budget deficits will total more than $3.8 trillion (18.7% of GDP) this year and $2.1 trillion (9.7% of GDP) in 2021,” according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. “We project debt held by the public will exceed the size of the economy by the end of Fiscal Year 2020 and eclipse the prior record set after World War II by 2023.”

Committee projections assume a strong economic recovery, and no changes in taxes or spending, so they are “almost certainly” underestimates.

While consumers have spent less during the pandemic, achieving a personal-saving rate of 33% in April, personal debt in the U.S. exceeds $20 trillion.

Warnings about the dangers of debt — government debt, consumer debt and corporate debt — were abundant before the triple crisis. During the pandemic, though, the debt has piled on at a rate that’s never been experienced before.

We’ve written plenty about the risks of government and consumer debt. It’s preposterous to think that we can continue to add to the IOU of $811,000 per taxpayer without serious consequences to our economy and our quality of life. And every consumer should know by now that debts must be paid or property will be repossessed and credit scores will be damaged.

But what about U.S. corporate debt, which comes to nearly $10 trillion today?

As The Wall Street Journal reported, “The coronavirus pandemic hit U.S. businesses at a bad time. Companies had loaded up on debt after years of low interest rates, buyouts and increasingly lax lending standards.”

Corporate borrowing is often bankrolled by collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), which are used to bundle risky corporate loans and turn them into supposedly safe bonds. Sound familiar?

With debt-heavy companies like Neiman Marcus, Hertz and J.Crew going bust, CLOs are becoming increasingly volatile.

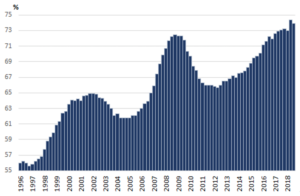

And the conditions that have led to increased corporate debt and higher volatility affect non-CLO debt as well. Demand for investment-grade debt has grown, but BBB-rated bonds, which are the lowest category of investment-grade bonds, now account for more than half of the market, according to Business Insider. That’s up from 17% in 2001.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that in a recession half as severe as the 2008 financial crisis, corporate debt-at-risk (debt owned by companies whose profits can’t cover interest expenses) could reach $19 trillion, or almost 40% of total corporate debt in major economies.

Corporate debt can “amplify shocks,” according to the IMF, “as corporate deleveraging could lead to depressed investment and higher unemployment, and corporate defaults could trigger losses and curb lending by banks.”