Part one of a two-part series.

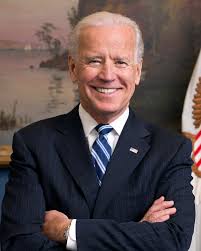

“Act big,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said at her confirmation hearing. And President Joseph R. Biden is doing just that.

During his first day in office, he signed 10 executive orders to expand testing and vaccine availability, reopen most schools within the next 100 days, and administer 100 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines by the end of April. (It turns out that the U.S. was ahead of the 100 million dose goal when President Biden took office, but there have been substantial delays.)

That’s all to the good, if it breaks the government delays that have been holding back vaccine administration.

“We have come to accept a public-performance culture of muddling through,” Daniel Henninger wrote in The Wall Street Journal, “but the vaccination rollout — with the whole country focused on this one thing — is showing people how inadequate and dangerous the status quo is. If government at so many levels can’t do something this straightforward — two injections — what can it do?”

Operation Warp Speed has been an extremely successful public-private partnership, with U.S. pharmaceutical companies developing new vaccines in record time. But the “public” part of the process has not lived up to expectations.

If President Biden’s executive orders don’t change that, perhaps his American Rescue Plan (ARP), which was proposed before he even took office, will. Adding $1.9 trillion in spending, it indeed acts “big,” but, as written, it would add considerably to the federal debt and could hurt, rather than help, the economy, which grew by 4% in the fourth quarter of 2020.

ARP proposes an additional $160 billion for a national vaccine program, including $20 billion for distribution, and an additional $50 billion for expanded testing. The plan also calls on Congress to invest $170 billion in K-12 schools and higher education, including $130 billion for schools to safely reopen.

It also includes stimulus checks of $1,400 for all Americans, an additional $100 to $400 per week in federal unemployment benefits through the end of September, $350 billion in aid to state and local governments, a national minimum wage of $15 per hour, expanded paid leave and increases in the child tax credit.

What Stimulus?

The sooner Americans are vaccinated, the quicker the economy can reopen. And, when it does, pent-up demand could help ensure a rapid recovery. Last spring the economy began to reopen and the economy grew at a record pace of 33.4%.

But ARP primarily seeks to stimulate the economy by spending lots of money. Keynesians believe that government spending, not private investment, is the key to economic growth. And Keynesian-minded politicians, whose power increases along with the federal budget, are ubiquitous in Washington, so spend we must.

During the financial crisis, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 was passed to stimulate the economy. It appeared to have little impact, as the economy grew at an average rate of 2.3% for eight years.

Keynesians believe the $836 billion spent — which made it the largest spending bill ever at the time — was not enough. In other words, it failed, because it didn’t act big enough.

Congress doubled down on stimulus spending last year with the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES). Other spending appropriations and legislation approved before CARES, such as the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, cost hundreds of billions of dollars. An additional $0.9 trillion relief package was approved in December, bringing the total pandemic-related spending close to $4 trillion.

Isn’t that enough? In comparison, Congress spent $4.17 billion to fight H1N1 in 2009. The Centers for Disease Control estimate 60.8 million Americans had H1N1 with 274,304 hospitalizations and 12,469 deaths. To date, the number of COVID-19 cases in the U.S. is exceeds 26 million with more than 440,000 deaths.

Granted, COVID-19 is even more serious that H1N1, but spending more than $5 trillion on COVID-19 — nearly 1,500 times what was spent on H1N1 — seems excessive, even when you factor in the cost of reopening the economy, which is already recovering.

As states lifted their economic lockdowns last spring, the economy grew at a record rate of 33.4%. It can be argued that CARES spending contributed to that growth, but even if that argument were correct, will more spending have the same impact?

For spending to stimulate, there must be demand for the funds being spent. Yet former U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin returned $455 billion in unused CARES funds that had been designated for Federal Reserve facilities and direct loans from the Treasury.

Before spending $1.9 trillion, it’s worth analyzing the potential benefit gained from that cost. One important consideration is that it will bring the U.S. government closer to insolvency.

Even without trillions in new spending, the federal debt will soon surpass $28 trillion. Interest rates are near zero, but it’s costing nearly $400 billion a year to service the debt. We’d have far fewer struggling families if that money were used elsewhere.