Part one of three.

Good things happen even in a bad year. In January, we wrote about many of the good things that happened in the abysmal year of 2020, but there’s one we skipped — the rejuvenated initial public offering (IPO) market.

“The coronavirus pandemic turned the typical rhythm of the IPO market on its head, with $67.3 billion raised in the fourth quarter,” according to The Wall Street Journal. “That amount is roughly six times the total for the first three months of the year.”

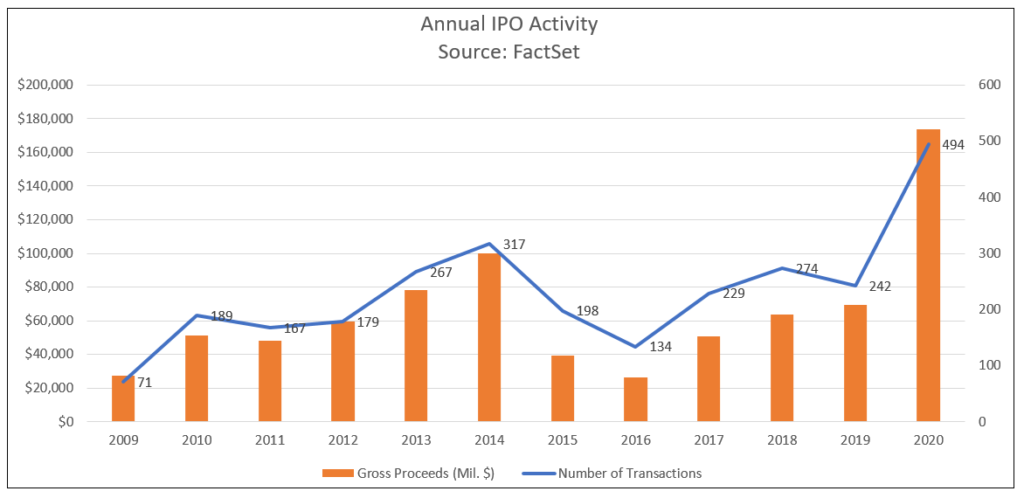

FactSet reported that 494 IPOs took place in 2020, which is more than double the number for 2019. The Journal quoted Dealogic, which reported that companies raised $167.2 billion through 454 offerings on U.S. exchanges in 2020 through Dec. 24, which was 55% higher than the 1999 full-year record of $107.9 billion, which was raised at the height of the dot-com boom.

And that atypical rhythm has continued to boom in 2021. As of March 4, 60 IPOs have been priced this year — a 160.9% increase from a year ago, according to Renaissance Capital. Total proceeds raised were $21.9 billion, a +227.4% increase from last year. Companies such as Robinhood and Coinbase are among those planning IPOs this year.

The Pre-Unicorn Era

Before the millennium, IPOs were the cornerstone of the U.S. economy. IPOs were how small businesses became big businesses. Companies would “go public” and raise the capital they needed to grow.

Companies with valuations in the tens of millions of dollars were going public. There were no unicorns — companies not yet public with valuations exceeding $1 billion. Today, there are 242 unicorns in the U.S. alone.

An IPO was the ultimate creator of wealth. Founders and employees of start-ups, who typically toiled for years to get to that stage, were able to monetize their sweat equity and convert it into financial equity. They often became very wealthy.

IPOs also meant opportunities for investors, who could buy stock in a newly public company in the hope that it would become the next Microsoft, the next Amazon, the next Apple or the next Google. By sharing the risk, they could also share the wealth.

The number of IPOs fell for many reasons, including the cost of compliance with the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and other regulatory requirements, the dot-com bubble, the financial crisis and a lack of research for small company stocks after a legal settlement in 2003.

Companies merging, delisting or going out of business reduced the number of public companies. From 1996 to 2016, the number of publicly listed companies in the U.S. fell by half to 3,600, down from 7,300, according to Credit Suisse. IPO activity peaked in 1996, with nearly 700 IPOs in the U.S., but in 2017, the number dropped to barely 100, the CFA Institute reported.

The rejuvenated IPO market is one again creating significant wealth. Nasdaq, which added 300 companies in 2020, reported that the average IPO stock was up more than 50% by the end of the year.