Part one of a two-part series.

It took nearly a decade for the Federal Reserve Board to reach its inflation target of 2%.

Now that the target has been not only reached, but surpassed, we’ll learn whether the Fed can be more expeditious in bringing the rate back down to its 2% target, especially given its ongoing commitment to its zero interest rate policy (ZIRP).

We have our doubts. The Fed didn’t instill confidence in achieving its goal when it changed its target to an average of 2%, which enables the Fed to average in inflation below 2% with inflation exceeding 2%.

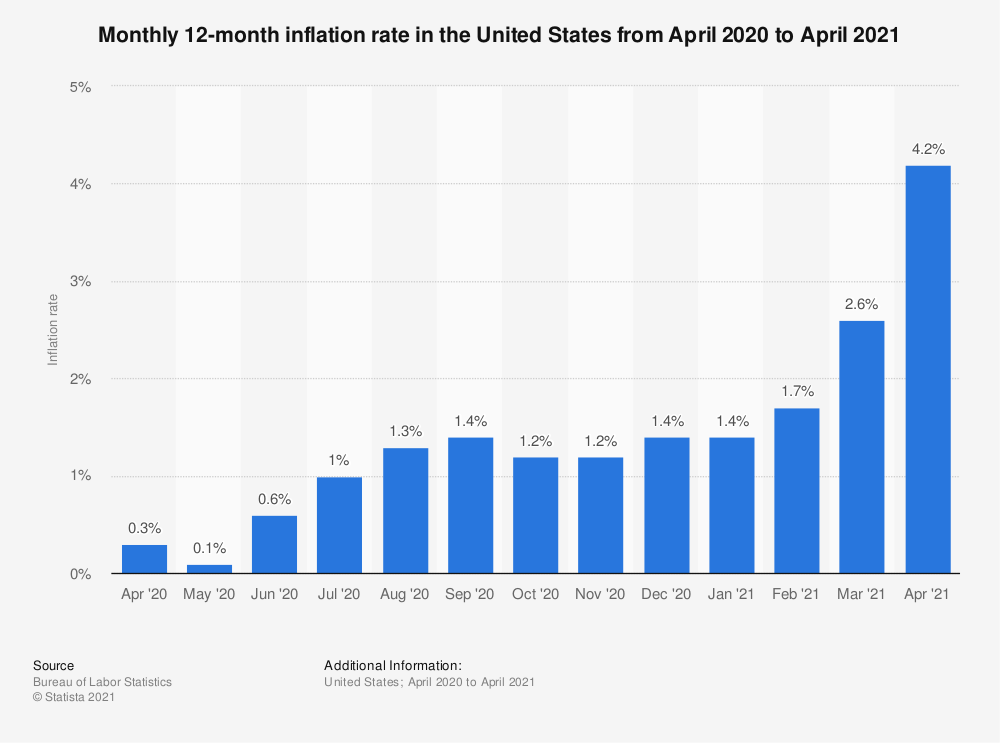

Such legerdemain was no doubt needed because the Fed anticipated a month like April. In April, Consumer Price Inflation rose 4.2%, which was the fastest rise in inflation in more than 12 years. The previous month, the inflation rate was 2.6%; that’s a 61.54% increase in just a month. And, according to Phil Gramm and Rick Scott, writing in The Wall Street Journal, “The core inflation rate, excluding food and energy, on an annual basis rose in April by 11%, a rate not exceeded since June of 1982.”

Not to worry. Fed Chair Jerome Powell says high inflation is “transitory.” Prices have been suppressed because millions of people were not working in the early days of the pandemic and they are rising now, because of the perceived near-end of the pandemic.

One reason Powell can claim that the recent rise in inflation is “transitory” is that it is due in part to supply chain issues — e.g., many parts and materials are unavailable, so rising demand as the economy recovers is outstripping supply. The prices of many commodities, such as lumber and copper, have been rising rapidly. The Fed suggests that will change as economies reopen worldwide.

Not So Transitory

But there are two other not-so-transitory factors that are also boosting inflation — Fed policy and government spending.

The Fed and the Biden Administration have been telling us that we need more “stimulus” — i.e., an unsustainable level of spending — along with continuing purchases of trillions of dollars in bonds to help the economy recover from the pandemic, even though the economy has recovered to the point where it should fare well without government assistance.

The pandemic recession during the second quarter of 2020, when gross domestic product (GDP) dropped 31.4%, was all but erased by year’s end, as gross domestic product (GDP) increased at a record rate of 33.1% in the third quarter, followed by a 4.3% increase in the fourth quarter. The estimate for the first quarter of 2021 is 6.4%. That’s well above the post-World War II average of 3.3%.

So why continue to pursue bond buying and multi-trillion dollar spending bills?

Easy Money Forever

The easy money policy followed by the Fed since the Great Recession in 2007 means that there are trillions more dollars in circulation than there were before the financial crisis. When the supply of money increases, the value of each dollar typically falls.

The money supply (M2) has grown 24.6% over the past year, which may be a postwar high, according to Gramm and Scott. In 1978, when the money supply grew at half that rate, inflation shot up to 13.4%.

Meanwhile, the Fed continues to add to the money supply by purchasing about $80 billion worth of Treasury debt and $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities a month. The Fed’s bond portfolio has increased from $870 billion in August 2007 to nearly $8 trillion today. The Fed decreased its assets to $3.8 trillion between October 2017 and August 2019, but they’ve doubled since then.

In spite of the recovering economy, the Fed has said it expects to keep interest rates near zero through 2023, which means bond buying will continue.