2013 markets were full of bull.

The economy continued to sputter along, growing at about 2%, unemployment remained high and corporate profits were mediocre. Yet the S&P 500 index rose a staggering 29.6%, its best performance since the go-go-days of 1997.

So what sort of bull drove this bull market? The Federal Reserve Board’s quantitative easing (QE) program, high-frequency trading and exuberant investors who shifted into stocks with renewed confidence.

When Fed Chair Ben Bernanke hinted in May and June that The Fed might start pulling back on its bond buying soon, the market initially fell and interest rates rose. But ironically, rising rates drove investors out of bonds and many invested further in stocks, pushing the market even higher.

When Fed Chair Ben Bernanke hinted in May and June that The Fed might start pulling back on its bond buying soon, the market initially fell and interest rates rose. But ironically, rising rates drove investors out of bonds and many invested further in stocks, pushing the market even higher.

More Bull in 2014?

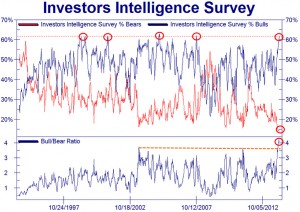

As 2014 begins, the bullish sentiment continues. More than 60% of those surveyed by Investors Intelligence are now bullish and the bull-bear ratio is at a record level of more than four.

Bullish sentiment at this level is typically a good thing, though, as high investor enthusiasm typically leads to a drop in the market. When investors are at their most bullish, that’s when the stock market usually drops.

Breaking a Trend

The stock market party may have, in fact, ended with 2013, as U.S. equity indices suffered their biggest loss on the first day of trading since 2008. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq were each down nearly 1% for the day.

For each of the past five years – since the start of QE – the market rose by an average of more than 2%. This year’s start, then, is down 3% from the recent average.

To Fight or Not Fight the Fed

Zerohedge calls the current economy the Fed’s Frankenstein Economy, as the Fed breathes life into it by boosting the stock and bond markets.

“In other words, having created a Frankenstein economy that depends on unlimited credit pumping, (some believe) the Fed can control its monster with uncanny finesse,” according to Zerohedge.

While Dr. Frankenstein has jolted the markets higher for five years, that doesn’t mean the Fed can continue to do so for the next five years. One reason could be “tail risk,” the unintended consequences of central planning.

It was tail risk that caused the financial crisis in 2008, as former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan recently suggested in Foreign Affairs.

So, Zerohedge asks, “are there no ‘tail risks’ or unintended consequences to leaving the money spigot fully open for five years running?”