You’ve probably heard that corporate America is swimming in cash. Something like $4 trillion worth of it. And once corporate America starts spending it, the economy will boom again, jobs will be created, GNP will soar and the stock market will boom ever higher.

Corporate cash is the good news. Corporate debt is the bad news.

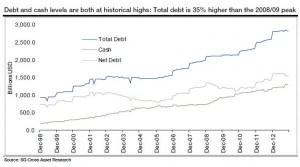

While cash is at record levels, corporate debt now exceeds the level it was at in 2008 and 2009. In case your memory is really short, that’s when America was wondering whether its financial system would survive.

But temper your nostalgia for those bad old days. When we say “exceeds,” we mean that corporate debt is 35% higher than it was then.

Net debt – what you get when you subtract cash from total debt – has been climbing steadily for American companies since 1998, as the chart shows. It doesn’t mean corporate America is insolvent (not yet, anyway), but it does have nasty implications for future corporate growth, profitability, unemployment and income growth.

Given all of that cash on hand, some are making heady predictions about accelerating capital expenditures. Goldman Sachs’ David Kostin predicted that capex spending will grow 9% in 2014, compared with 2% growth in 2013.

He may be right, given the need to replace aging and outmoded equipment, but a prediction is only a prediction. And more capex spending will mean less cash for paying down corporate debt.

Debtor Nation

Maybe American corporations are increasing their debt because they were feeling left out. Debt is rampant everywhere else in today’s economy:

- The federal debt is now just under $17.5 trillion. Yes, there’s a debt ceiling, but in case you haven’t noticed, it gets raised every time the federal government wants to spend more money. Don’t forget, too, that the federal government has nearly $100 trillion in unfunded liabilities to cover Medicare, Social Security and government pension obligations.

- Quantifying state and local government debt isn’t easy, but the U.S. Census Bureau reported last summer that it reached $2.9 trillion in 2011. It’s presumably above the $3 trillion mark today.

- Household debt has been held in check – relatively speaking – since the financial crisis began in 2008, but it’s now rising again. As The New York Times reported, “Total household debt grew steadily before the financial crisis and peaked in 2008, at $12.7 trillion, at a moment when, it is now clear, Americans were dangerously overleveraged. It then decreased to a low of $11.2 trillion before starting to edge back up in the second half of last year.”

Paying It Back

Debt provides an opportunity for businesses to grow. And it can pay for things we otherwise would be unable to afford, such as a home or a college education.

But there’s one problem with debt. When you borrow money, someone has to pay it back.

Money used to service debt provides no economic benefit. It can’t be used to invest in capex or stocks or dinner at your favorite restaurant. Borrowing reduces your future disposable income by the amount you borrow, plus compounded interest.

The net result is that paying off debt lowers your standard of living if you’re a consumer and makes you less profitable if you’re a business.

The government is different, though. It has choices – it can continue raising the debt ceiling, which will cause the cost of servicing the debt to increase; it can reduce spending, which is politically unpopular; it can take steps to encourage economic growth and bring in more revenue, but no one in government seems to have that ability, or it can raise taxes, which is also politically unpopular, but tends to be the course of choice.

Every choice, though, comes down to this – consumers and businesses must not only pay off their own debt, they must pay off government debt. So what does that cost us, on top of our own debt?

A study by the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget noted that interest payments on the federal debt in 2013 totaled about $255 billion. That’s not bad, when you consider that it’s about the same amount that was being paid in 2006, when the debt was only about 40% as large as it is today.

The difference, though, is that today’s interest rates are historically low. In January, the U.S. Treasury was paying 0.01% interest on three-month T-bills, compared with a historical average of 3.3%, and 2.98% on 10-year notes, compared with a historical average of 5.2%.

Interest rates will eventually double or even triple, even as the federal debt continues to increase. And it’s a certainty that the federal debt will continue to increase.

Currently, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal debt will reach $25 trillion by 2021, but the CBO historically has underestimated federal debt in its forecasts by about 40%, so the federal debt could be $35 trillion by then.

It’s not unrealistic to expect that the cost of servicing the federal debt will rise to $1 trillion a year by then. That’s $1 trillion a year spent just to tread water. It will not create jobs, keep us safe or repair our highways.

Given the cost, you’d better pay off all of your debts now, so you can afford to keep the federal government operating in 2021. That’s less than a decade away.