Few investors today would consider investing in long-term Treasury bonds.

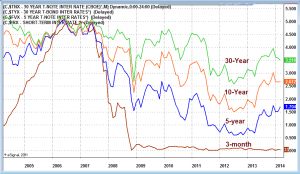

The yield curve, which measures the spread between interest rates for short-term and long-term bonds, is not as flat as it has been in recent years, but that’s faint hope for investors.

A 10-year Treasury is still yielding less than 3% interest. If the Federal Reserve Board achieves its goal of pushing inflation up to 2%, the real interest on a 10-year bond purchased today will be under 1%, payable at maturity.

If the Fed overshoots its goal and inflation moves higher, which is highly likely, a 10-year bond would produce a negative yield. What’s the probability that inflation will remain lower that the current yield on a 10-year Treasury over that entire period?

The U.S. has not had a period when inflation remained below 3% for a 10-year period since the days of the Great Depression. During the period of recession then slow growth that we’ve experienced since the financial crisis began in 2008, inflation has remained low and the Fed’s focus has been on fighting deflation. But when the economy improves and normal growth returns, inflation is likely to move significantly higher, as higher inflation is a byproduct of a healthy economy.

Long-term bonds are a risky investment that offers little potential gain, so if you’re buying bonds, it makes sense to go short. Unfortunately, the Fed doesn’t always make sense.

Fed Still Propping Up the Market

At the same time the Fed has been tapering its purchase of bonds, it has been lengthening the maturity of its purchases. As George Melloan wrote this week in The Wall Street Journal:

- Bonds with maturities of more than 10 years now account for 26% of the Fed’s portfolio, compared with 18% only four years ago.

- Maturities between five and 10 years now account for 37% of the portfolio, versus 26% in 2010.

- Maturities from one to five years have dropped to 37% from 42%.

- Short-term notes of 91 days to a year accounted for 23% of holdings before the 2008 financial crisis. Today, the Fed holds none.

Melloan believes the shift from short-term purchases to long-term purchases is propping up the stock market, which has remained relatively stable – with some fluctuation, of course – in spite of the Fed’s announcement that it will continue cutting back bond purchases by $10 billion a month.

Paraphrasing John Butler, a fund manager for Amphora Commodities in London, Melloan writes that “buying a greater proportion of longer-dated securities from the banking system and thus relieving bankers of risk means that monetary policy may be no more tighter than it was before tapering.”

While current stock prices are synthetically produced, rather than a reflection of fundamentals or economic strength, high stock prices sure beat low stock prices – but what are the consequences of current Fed policy?

In purchasing long-term bonds, the Fed is relieving banks and the Treasury of some of its long-term risk. But when the Fed takes on risk, so does our monetary system, American taxpayers and the world economy. We’re in the dark about how purchasing bonds that are almost certain to drop in value helps the U.S. economy, even if it does help U.S. banks.

“The Fed has put itself in a position that offers no easy way out,” according to Melloan. “If credit demand rises and that huge holding of excess bank reserves finds its way into the global economy, it could trigger inflation in excess of the Fed’s strange 2% target, and it could happen fast.”

There is an upside to going long, though. While the Fed has been buying bonds, in part, to boost inflation, by moving its purchases to long-term bonds, it will not have an incentive to help keep inflation in check.

We’ll see how that works out in the next few years.