The average recovery since the end of World War II has been 58 months. The current “recovery” has just reached that milestone.

So maybe we should be celebrating. But what’s to celebrate?

If you were to define “recovery” as a period when gross domestic project (GDP) increases from one quarter to the next, yes, we’ve been in a recovery. But a recovery is typically reflected by a period that also includes, among other things, low unemployment, strong consumer spending, increasing income, higher inflation and strong manufacturing.

Most of those signs of recovery have been either barely visible or missing, and GDP has been growing about as fast as a bonsai tree.

This has been, and will likely continue to be, the recovery that no one noticed. It’s a recovery in name only, as for most Americans it doesn’t feel much different than a recession. Consider what’s been happening:

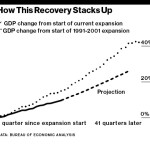

GDP. Some are calling this recovery The Great Moderation, but if anything, it’s The Not-So-Great Moderation. If your goal is mediocrity, this recovery is for you.

As we’ve reported previously, GDP has grown at an average of 3.3% a year since World War II ended. GDP growth has been below that average throughout the current recovery. GDP grew 2.5% in 2010, 1.8% in 2011, 2.8% in 2012 and 1.9% in 2013.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that GDP will grow at an annual rate of 3% from the fourth quarter of 2013 through the fourth quarter of 2014, with a similar rate of growth projected through 2017.

The non-partisan CBO is typically wrong, though, and, as a government entity tends to make the government look like it’s performing better than it is. Even if it’s right, though, 3% growth is below average.

We should also keep in mind that the economy is cyclical. With the recovery reaching the average lifespan of the typical recovery, we may be headed for another recession.

Unemployment. Other than the miraculous drop in the unemployment rate just before the Presidential election, when’s the last time you heard about a significant drop in the unemployment rate?

This past week, 329,000 people in the U.S. filed for unemployment benefits – a jump of 24,000, which is an increase of more than 6%. It may have been a result, in part, of temporary layoffs related to Easter, but the four-week average also jumped by 4,750 to 316,750, according to the Labor Department.

In January, we reported that more than 102 million Americans were not working – that was a record, in spite of the decreasing unemployment rate. The unemployment rate has been decreasing because many people are retiring, giving up on looking for work or taking part-time jobs to make ends meet. It looks like we’re setting yet another record.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, in a refreshing bit of honesty, had this to say: “Early in the recovery, firms continued to have the lowest rate of job creation on record, and fewer new firms were created in 2009 and 2010 than in any other time in the previous 30 years. Although the unemployment rate fell faster than expected in the latter part of 2013—roughly four-and-a-half years into the recovery—hiring rates at firms were still relatively subdued.”

Salaries. In 1986, four years after the 1981-82 recession, hourly wages averaged $8.80 (in 1982-84 dollars). Today, four years after the Great Recession, they’re at $8.88. That’s an increase of just 1% over 28 years. Worse still, since the recovery began, wages have fallen 2.6%.

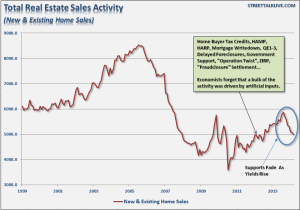

Housing. Last year, it seemed that a housing recovery was being held back only by the lack of inventory. This year, though, it’s clear that all is not well. Sales in March were down 14.5%, dropping to their lowest level in eight months. Sales were also down 13.3% from a year ago.

What happened? While incomes have been dropping, home prices and interest rates have been rising, pricing many Americans out of the market, but that’s only part of the story.

Under the Dodd-Frank Consumer Protection Act, many consumers are being so well protected, they can no longer qualify for a mortgage. According to Bruce Taylor, president of ERA Key Realty Services, before Dodd-Frank, lenders were providing mortgages to borrowers who couldn’t afford them, and now they’re not providing mortgages to those who can afford them.

“This astonishing bit of legislative progress is the result of provisions in the law that allow consumers who obtain a mortgage to later sue the lender on the grounds that they should not have qualified for a mortgage, because they can no longer afford it. As lenders do not have the ability to see into the future, they have instead largely decided to grant mortgages only to borrowers who meet the most stringent qualifications.”

Manufacturing. We’ll take good news where we can get it. It isn’t much, but the March PMI® increased 0.5% to 53.7% in March, recording an expansion for the 10th consecutive month. Likewise, the New Orders Index increased 0.6% to 55.1%. The nudge upward includes results from petroleum and coal products, which has been boosted by the development of hydraulic fracturing.

Record Regulation

Why has the economy performed dismally, in spite of unprecedented efforts by the Federal Reserve Board to revive it?

A clue can be found in the Federal Register, which in 2013 grew by a record 26,417 pages.

As The Wall Street Journal noted, “Congress may be mired in gridlock, but the federal bureaucracy is busier than ever. In 2013 the Federal Register contained 3,659 ‘final’ rules, which means they now must be obeyed, and 2,594 proposed rules on their way to becoming orders from political headquarters.”

Four of the five highest totals for new regulations added to the Federal Register have occurred under the Obama Administration.

The Competitive Enterprise Institute’s Wayne Crews estimates that regulatory compliance has an economic impact of $1.9 trillion a year.

Many economists and government officials believe that economic growth of 2% a year is the new normal. If the regulatory burden continues to increase at the current pace, they’re probably right.