The end is near.

The Federal Reserve Board has now put a date on the quantitative easing apocalypse, letting us know that bond buying will end in October – unless the central bank changes its mind, of course.

The October ending is not unexpected. The Fed has been cutting back bond purchases by $10 billion a month since last year and it doesn’t take a math wizard to figure out that there will be nothing left to taper post-October.

Yet this news, reported in the just-released minutes to last month’s meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee, is being treated as a revelation. It was, for example, the lead story in The Wall Street Journal, which typically doesn’t lead with news that was discussed last year and made official at a meeting that took place a month ago.

The real news, though, is what wasn’t discussed – the end of near-zero interest rates. As a result, rather than pushing yields up and bond prices down, release of the meeting minutes had the opposite impact.

As Barron’s announced, “Bonds just pulled the market equivalent of a delayed handoff, as Treasury yields held steady for the first few minutes following the release of the Fed’s latest policy meeting minutes and then started falling pretty sharply. The 2-year yield has fallen to 0.504% in the past half-hour while the 10-year yield has dropped to 2.556% from 2.569%, per Tradeweb data.

“The market’s take seems to be that the minutes don’t really offer anything that would move the needle much on any Fed-related rate-hike expectations. That in turn is being received as dovish news, since there were some fears that the minutes might offer hints that some Fed members might be looking to hike rates sooner.”

The minutes didn’t say much, so tea-leaf readers referred to them as “upbeat” and “dovish.”

Perhaps James Bullard, president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve, was bound and gagged before the meeting. You may recall our recent post noting that when he suggested that a rate hike may take place in the first quarter of 2015, the Dow dropped by 100 points.

In the past, the Fed has moved markets based on its actions. Now it’s moving markets based on its inactions. Who needs forward guidance when doing nothing can give the bond market a boost?

Phantom Boosts Bonds

Bond yields also all but ignored the recently announced drop in unemployment from 6.3% to 6.1%. Granted, that’s the U-3 rate, but given recent history, a 0.2% drop in unemployment is good news.

Many bond-market analysts believe heavy demand from overseas buyers – especially China – is pushing bond prices higher.

David Woo, head of global rates and currencies research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, believes a “phantom bond buyer” is boosting the U.S. market and he believes the phantom is China. However, he expects that Chinese purchases will slow in the second half of 2014 and, combined with U.S. economic improvement, will push yields on 10-year notes from the 2.6% range to as high as 3.5%.

With global growth slowing and U.S. economic predictions continuing to have little basis in reality, we don’t expect the 10-year yield to move beyond 3% anytime soon.

The Fed’s next move will be to increase short-term rates. Unless the Fed loses control, any increase in interest rates will take place gradually.

That’s a big “unless,” of course. The Fed’s tapering of bond purchases has had surprisingly little negative impact on the markets and the stock market has, in fact, continued to set records.

The hope is that an improving economy will offset any impact from increasing interest rates, but currently any mention of interest rates makes the market skittish. Another worry is the impact the Fed will have when it begins selling off bonds from its $4.5 trillion portfolio.

The impact of five years of easy money policy is anything but easy to gauge.

Another Mouse Roars

One reason for the slowing global growth we referred to is that new problems are arising more quickly than old problems can be resolved.

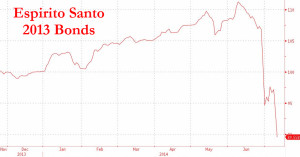

As just one example of the continuing global economic malaise, consider what’s happening in Portugal. Espirito Santo International SA, which is among Portugal’s largest lenders, is in “serious financial condition” and “ ‘ponzi-like’ maneuvers have left the bank unable to pay its bonds, causing bond prices to drop to record lows.” Could yet another European Union bailout be on the way?

Of course, a country the size of Portugal is unlikely to cause major economic problems, right? Well, maybe not. Portugal has a population of about 10.5 million, just over a half million less than Greece.